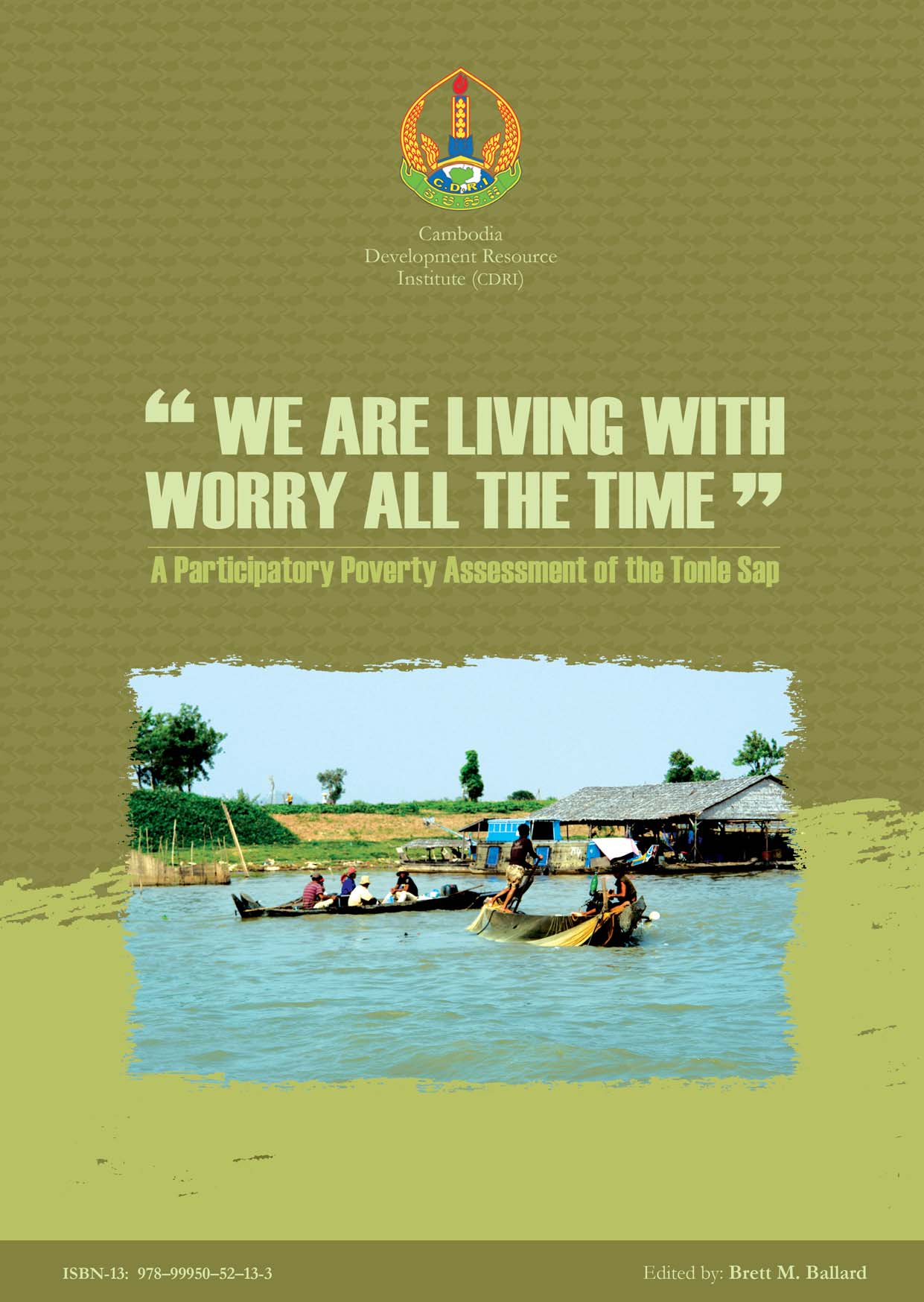

“We Are Living with Worry All the Time” A Participatory Poverty Assessment of the Tonle Sap

Abstract/Summary

Executive Summary

The Participatory Poverty Assessment of the Tonle Sap (PPA) has been undertaken by CDRI in collaboration with the National Institute of Statistics (NIS) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The study employed qualitative research methods covering 24 villages in the six provinces around the Tonle Sap Lake. The main objective of the study has been to provide policy makers, donors, and civil society with a deeper understanding of (1) the relationship between poor people’s livelihood strategies and their use and the management of natural resources, (2) the gender dimensions of poverty, and (3) the role of local governance in poverty reduction.

The PPA study shows that many of the poor and the destitute in the Tonle Sap region are not benefiting from Cambodia’s rapid economic growth, and often appear to be beyond the reach of public policy. This observation poses serious challenges for the government and its development partners in delivering effective poverty reduction outcomes in line with the objectives set out in the National Strategic Development Plan aimed at meeting Cambodia’s MDGs.

The study shows that the poor and the destitute are increasingly dependent on land and water based natural resources to sustain their fragile livelihoods. Several years of draught and flooding, along with poor soils and a lack of water management capacity, however, has eroded farming productivity, while people’s traditional access to forests and fisheries is increasingly subject to the pressures of a growing population and to conflict with local elites and powerful actors from outside the village. As a result, a greater number of the poor are selling their labour locally or migrating elsewhere within the country or to Thailand and Malaysia in search of employment.

The study also shows that the poor and the destitute lack access to important infrastructure, such as clean drinking water, and are routinely excluded from education, vocational training, and health care services because they are not able to pay for such services. As a result of the high costs associated with informal fees for teachers, the children of the poor, especially girls, tend to stop attending school at an early age. The high costs of healthcare are forcing more of the poor and the destitute into selling assets such as land to pay for health services, thus pushing them closer to landlessness and into deeper poverty. The poor and the destitute are also excluded from social services because they lack information and knowledge about such services and their rights to obtain such services. In this sense, the situation of the poor, and especially the destitute, becomes self-perpetuating.

The study also shows that many people perceive that personal security is fragile and that the poor and the destitute are especially vulnerable to various forms of domestic and public violence. Women’s fear of rape and parental fears associated with the perceived safety risks in sending their daughters to school have been a constant refrain in many PPA villages. In all the villages, people also observed instances of youth and gang violence. In some villages, people have observed drug and substance abuse among youth. In many villages, domestic violence against women is closely associated with poverty.

The study shows that local officials are routinely confronted with inadequate information, scarce resources, and ambiguous authority. Local officials are also frequently under pressure from powerful elites or high-ranking officials for special favours and services. Corruption at the local level is endemic, and prevents the poor and the destitute from obtaining social services and erodes their capacity to improve their livelihoods. The poor and the destitute are also excluded from decision-making processes, and receive little or no response to requests or opportunities for the redress of grievances. They tend to avoid government, while relying on civil society organizations and social networks for support. That the poor and the destitute may view certain government institutions as part of the problem, rather than the solution, should concern government agencies and other development stakeholders.

The PPA study also shows that the commune councils can work effectively in areas such as rural infrastructure involving the construction of roads and bridges. In some villages, the poor have also benefited from collaboration between local governance institutions and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in areas such as healthcare, extension services and small-scale credit. Such examples demonstrate that many commune councillors and other local officials remain committed to improving the situation of the poor and that improved governance at the local level is clearly possible when various stakeholders are able to cooperate.

Policy Implications

The PPA study has identified several areas where improved governance is required to achieve the government’s poverty reduction objectives. The most important priority areas concern the need for (1) more allocation and better targeting of agricultural and rural development inputs, (2) strong and impartial enforcement of laws and regulations governing access to and control over natural resource assets, and (3) more allocation and better targeting of social services, especially clean water and healthcare access for women, as well as expanded education and vocational training opportunities for all youth, with a special emphasis on women and girls. Other priority areas concern the need for laws and regulations that protect migrant workers and the enforcement of laws that promote public security, with particular attention to violence against women and drug use among youth. Overall, there is a real need to reduce the pernicious effects of corruption and strengthen the responsiveness of national policymakers and local officials to the problems and needs of the poor and destitute. Without a strengthening of public sector accountability, efforts to reduce poverty and improve the well-being of the poor and the destitute in the Tonle Sap region, and elsewhere in the country, will not be effective.

The delivery of services in support of agricultural and rural development is highly fragmented in the PPA villages. There would be a greater impact on well-being and poverty reduction if complementary packages of inputs, including irrigation, secure land titles, extension services and affordable credit, were provided to poor areas along with social services, such as affordable health care. This reinforces the need for better horizontal and vertical planning and coordination of efforts within government and between government, international donors, and NGOs. At the local and commune level, such approaches require that technical support and capacity building must be available from district and provincial offices as well as NGOs. There are now several examples of integrated community development best practices that could serve as models for replication on a wider scale.

Although national polices governing natural resources are designed to promote the sustainable management of land and water assets, poor implementation and enforcement at the local level are promoting the rapid degradation of the natural resource base and undermines people’s respect for public institutions. What is urgently required is stronger and more equitable enforcement of the rules and regulations that already constitute the policy framework governing natural resource management. There is also an urgent need to reconsider how conflicts can be managed in ways that provide the poor and the destitute with access to fair and impartial resolutions. This concerns local conflicts at the village level as well as conflicts involving outside interests, including the rich and powerful.

Special provisions need to be designed to promote better access to social services, including health and education, on the part of the poor, especially women. A greater share of the national budget must be urgently allocated for clean water and public sanitation, healthcare, education and vocational training, and public transport. Health insurance schemes for the poor and destitute need to be piloted and education scholarships for boys and girls of poor households need to be expanded. One avenue for channelling increased resources to the local level would be to increase the annual amount of inter-governmental transfers to the commune/sangkhat fund. A certain portion of such transfers could also be specifically designated for certain priority activities, such as clean water.

The ineffectiveness and lack of fairness associated with governance in the Tonle Sap region are largely matters of implementation and enforcement. This suggests that much more attention must be devoted to strengthening governance institutions at the local level in ways that promote better planning and enable more public participation, including women, reduce corruption, and increase public sector accountability and responsiveness. Steps must also be taken to improve dialogue between the people and their governing institutions in ways that build mutual trust and respect.

There are several ways for this to take place. The roles, responsibilities and authority of the commune councils, police and military need to be clarified. Empowering the commune councils to raise own source revenues and plan in response to local needs is another essential component of building stronger governance institutions at the grassroots. Such processes must include a strong capacity building component for local and sub-national officials concerning the planning and implementation of services in response to the needs of the poor and the destitute.

It is clear that the state, private, and civil society sectors all have certain strengths. The challenge for policymakers and other stakeholders in the Tonle Sap region, as in other regions of the country, is how to design and strengthen collaborative arrangements between all three sectors in ways that the comparative advantages of each are complimentary in support of ecologically sustainable pro-poor social and economic development.